Mangoes, MH370 and the military industrial complex: the hype and hypocrisy shaping conflict in the South China Sea

Hi-tech weapons are being used by China's coastguard on Filipino fishermen in disputed waters. Much larger weapons are being touted by Beijing to keep meddling Western warmongers at bay.

This article was originally published in November 2018.

===

In August 2007, six nuclear weapons were attached to a B-52 bomber and flown from North Dakota to Louisiana - the whole US north to south. After the plane arrived at Barksdale air base, it was left alone for hours with the warheads still attached. It was the first time since the 1960s that nuclear bombs were flown across America, but it got little mainstream media coverage.

The military insisted loading the nukes onto the plane was a mistake, forgetting the strict chain of command at US bases, where soldiers even need to sign out bullets. Moving a nuclear warhead would involve many signatures, including at least one from the White House. Six people from the Minot base in North Dakota - some linked to the chain of command - died in the weeks before and after the event and at least one death was suspicious.

The whole thing reeked of conspiracy and cover-up and was only really examined on alternative news websites, the kind internet giants are under pressure to silence because they spread “fake news”. With the first reports from base sources saying only five nukes were on the plane at Barksdale and the military insisting later there were six, it was suggested one may have been saved for a false flag operation that would be blamed on an enemy to justify a war.

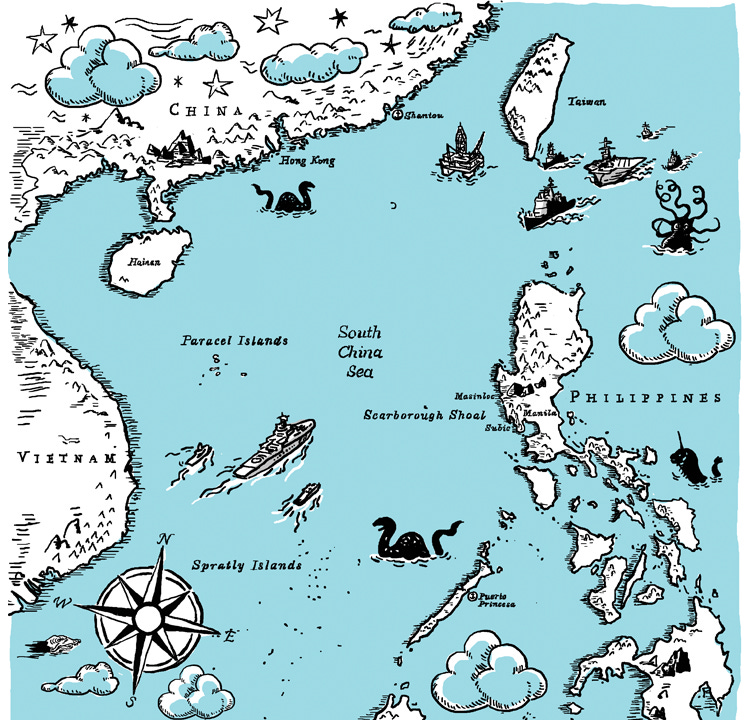

The same Boeing B-52s are now flying over disputed areas in the South China Sea. They are probably not armed with nukes, but even if they were, Washington might not admit it. So far, they seem to be part of US-led forces visiting the region because of what they see as Beijing’s colonisation of desert islands and reefs. In the Philippines, the possibility of the tension nearby escalating into conflict appears high, as the US and its allies hype the threat posed by China.

“Well just look at the Operation Iraqi Freedom. Up to now ... there’s still no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, so you can see the use of a threat to justify policy action,” says Filipino military historian Jose Antonio Custodio, referring to the widely-disputed justification former president George W. Bush gave for the US-led invasion in 2003.

Since the US left the Philippines in the 1990s, Filipinos have been concerned about China’s motives. Among them is Ashley Acedillo, a former congressman and ex-soldier. In 2003 and 2007, he and his army buddy Senator Antonio Trillanes and their comrades took over plush Manila hotels and tried to overthrow president at the time Gloria Arroyo but failed. Now “Ace” is a security analyst and worried about the Chinese developing disputed islands.

“Three of which are in our exclusive economic zone ... They have practically made these areas into fortresses. To what end? That’s the scary part. At a time when their rise - economic rise - coupled of course by the rise of their military power ... they’re already exhibiting this behaviour that we would not have expected from them because they’re our neighbours and we’ve had a long history. Every other Filipino has Chinese blood, including myself.”

Acedillo accuses President Rodrigo Duterte - and previous Philippine leaders - of not doing anything about China expanding its defences into their territory: “I have not seen any government effort to come up with a comprehensive long-term strategy in the face of this very tricky and complicated issue ... What I see would be a disastrous outcome for our country.”

The US and its allies have said they will maintain “freedom of navigation” in the South China Sea, a vital trade route that’s a bit smaller than the Bermuda Triangle. China’s takeover of the uninhabited reefs and desert islands may be linked to trade but seems a reaction to the so-called pivot to Asia championed by Barack Obama when he was US president.

In July, Britain said it would in the future start sending its new aircraft carrier to help Australia patrol the South China Sea. “This isn’t something we want to see as a flash in the pan but actually a commitment to the region,” insisted Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson at the time, going several steps further in December by hinting at plans to build a navy base somewhere in Southeast Asia.

“The United States, it comes in because of its treaty obligations to the Philippines,” Custodio explains. “The British are here out of their connections with the United States [and] they’re still trying to make themselves relevant to whatever geopolitical purpose and objective that they have.”

But as Britain protests China’s reclamations, a top UN court is pondering the UK’s almost identical claims to desert islands and reefs in the Indian Ocean that London grabbed from former colony Mauritius in the 1960s. The Chagos Islands include Diego Garcia, a tropical paradise Britain took then rented to the US for an air base and where B-52s took off to bomb Iraq and other places. To get it to the strategic grail it is, the UK government secretly got rid of the 2,000 or so residents by withholding food and medicine and reportedly even killed their pets to scare them away.

Diego Garcia appears prominently in conspiracy theories about lost Malaysia Airlines flight 370. The only wreckage of the plane recovered so far has been found in the general area. The last radar sighting showed the plane arcing towards the Indian coastline just north of Sri Lanka. People north in the Maldives claim to have seen a low-flying jet with similar markings to the carrier pass their islands about seven hours after it vanished. It has been suggested the Boeing 777 may have been taken over by remote control and flown somewhere with the passengers alive. Diego Garcia is seen as the most likely destination because of its history as a black site used to interrogate suspected terrorists kidnapped by US intelligence.

“Most of the circumstantial evidence, I believe, points towards an abduction of this plane,” Sarah Bajc, an American whose boyfriend was on the flight, told CNN at the time. “I don’t know why and I don’t know by whom, but I’m convinced that plane was taken by somebody ... It could be that every single person on that plane is an innocent victim in this and it was a military action of some country instead.”

Despite being equipped with some of the best military radar, tracking hardware and spy satellite technology on the planet, the screens at Diego Garcia never apparently picked up the plane. If MH370 was hijacked and flown there, the Americans and British would probably want the search to be in the opposite direction, which is what happened, with rescuers in the southern Indian Ocean finding absolutely nothing.

Relatives of the passengers launched a new bid in November to get the Malaysian government to resume the search after more suspected plane pieces were found on Madagascar’s coast. Transport Minister Anthony Loke Siew Fook said it needed more “credible leads” first.

Among those on the flight were staff from US tech firm Freescale Semiconductor - 12 from Malaysia and eight from China. Days before the disappearance, the company had developed a new electronic warfare tool and with its shareholders including the Carlyle Group investment firm - which has links to the families of George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden - conspiracy forums were buzzing with theories.

What happened to Freescale after the crash was largely ignored. In the year leading up to MH370’s disappearance, Freescale was developing high power radio frequency (RF) devices - including weapons - and positioning itself to be the only US-based supplier of a semiconductor used by the American military. By 2023, the semiconductor industry is projected to be worth nearly US$140 billion with nearly a third of the business from the Pentagon, according to the firm Strategy Analytics.

Almost a year to the day after the flight’s disappearance, Freescale was bought by Dutch rival NXP in a merger it said would make them a market leader worth US$40 billion. NXP paid roughly US$12 billion for Freescale, which it valued at US$16 billion. “We think we can drive the connected device market and be the leader in making all of our lives more convenient and safe,” NXP’s CEO Rick Clemmer told CNBC at the time, making clear the focus would be on consumer electronics. Strategy Analytics was concerned about the loss to Freescale of valuable defence contracts due to the merger. Less than two months later, NXP sold its potentially lucrative high power RF business - including “all relevant patents and intellectual property” from both companies - for a mere US$1.8 billion to Jianguang Asset Management, a subsidiary of China’s state-owned sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation.

For years, analysts and former military staff warned the US government it needed to focus its defences on the threat high power RF weapons posed. “New technologies might serve to challenge [America’s] advantage if an enemy can exploit them,” John Brunderman, a former US Air Force officer wrote in a 1999 report, because they could be “an effective defence against our standoff cruise missile and stealth technology”. Now Freescale and NXP’s high power RF weapon technology - including missile guidance and electronic warfare systems - is in the hands of the Chinese government and no doubt technicians at PLA weapon labs.

“The perception of a threat,” says Custodio, “spurs on the American side the need to research more and develop more and manufacture more cutting edge technology and hardware and military hardware to maintain [its] lead. All of those require funding and ... when the United States’ economy is not doing as well, you really have to justify a threat in order to ensure funding, so any threat ... Chinese hypersonic weapons or Russian military aggressiveness can be used to sustain a weapon’s development.”

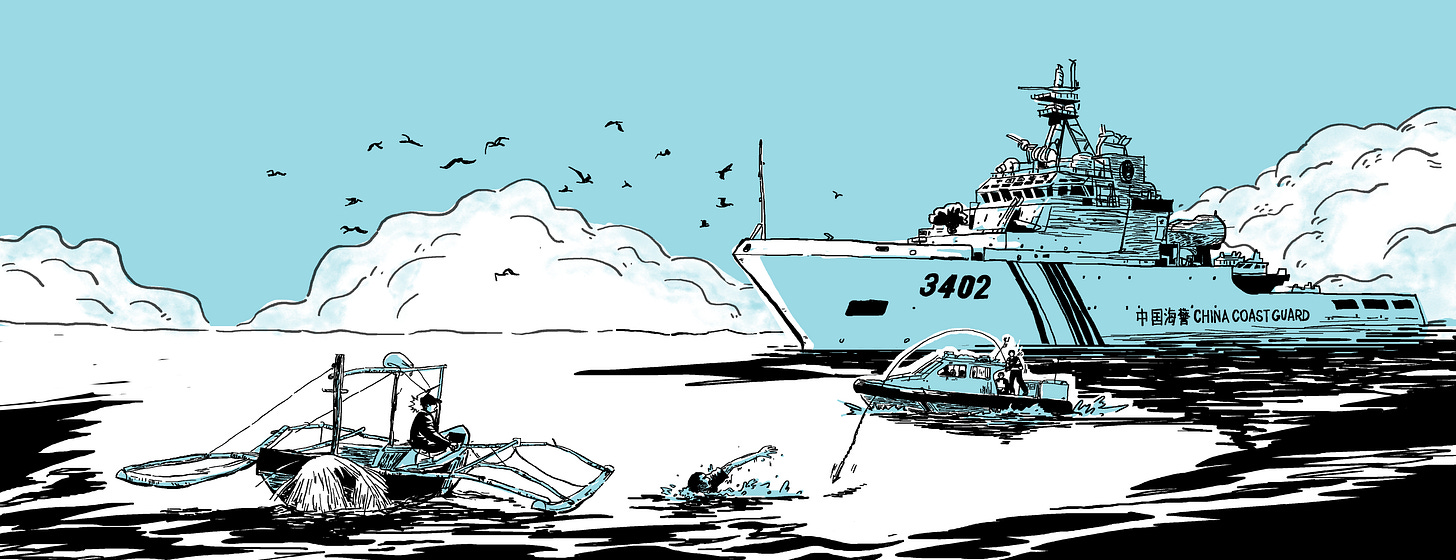

Popular uses for high power RF technology are direct energy weapons, devices firing sound or microwaves that are usually deployed for crowd control. During former Philippine president Benigno Aquino’s rule, China’s Coastguard was using sonic weapons on Filipino fishermen at Scarborough Shoal, one of the disputed South China Sea areas now controlled by Beijing.

That’s according to fishermen from Masinloc in Zambales province, a town famous for its mangoes, which the Guinness Book of Records once said were the world’s sweetest.

“About one mile before Scarborough Shoal, they are posting there, like water cannon [and] what they call ... supersonic weapon ... You cannot block over the ear... that kind of apparatus,” said Masinloc Municipal Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Management Council Chairman Rolly Bernal.

The world’s sweetest mangoes are now found south in Visayas. Rolly is still proud of the local fruit, pointing to trees on nearby San Salvador island and saying they will produce “the sweetest mangoes ever”. The island is the home of another fisherman Delfin Agana, who says he was attacked by Chinese Coastguard officers in December 2017. They threatened to kill him then stole his fish and equipment, he claims. “Woo-woo-woo,” he said, when asked about the noise made by Chinese sonic weapons.

The Philippine Coastguard said it knew about the sonic weapon claims but didn’t do anything because they were “not validated”. “The good thing is we are now talking [to China] and we are now establishing a line of communication where we can agree on certain matters,” said spokesman Armando Balilo.

Not much is known about China’s sonic weapons, but “dispersed energy weapons” can cause unknown injuries. “It’s a sound wave, it causes your body to vibrate,” a US military veteran told me at a bar in Olongapo, a couple of hours south of Masinloc. “It’s like if you stand in front of a speaker at a rock concert, you’re going to feel the vibration. You get up to the ultrasonic frequencies...” he said, then shrugged. The veteran, who did not want to be named, uses high frequency sound to clean industrial machines – “grime and stuff off of engine parts”. Depending on their frequency, he said, they can cause organs to vibrate if used on humans, so are “potentially bad”.

When the US had its base in nearby Subic, prosperity spread throughout the surrounding areas, as well as neighbouring Pampanga province, home to the former air base in Clark. Sipping beer in a veterans club in Olongapo, retired US Navy officer Tom Burnett said: “People were happy when the navy was here. They were well taken care of ... When the aircraft carrier battle group came in you got 8,000-9,000 sailors running through town.” Now, on a rainy Saturday, the streets and bars are virtually empty. “All those bars and everything ... they all closed up.”

Over at the bar, veteran Clifton Wilsey, another expat who fought in the Vietnam war for 27 months, spoke of the ghosts of the war dead wandering Clark hospitals and lamented the US leaving the Philippines in the 1990s. “[It was] a sad day for the Americans, especially the guys that were lower level guys ... this was a great assignment. I mean, I’d say 20 per cent of all the GIs that came here married a Filipino.”

According to Acedillo: “At the time ... our fishermen could fish wherever they wanted to ... They practically had the run of the whole area.” But Burnett said the shoal, like the disputed Diaoyu Islands which China and Japan both claim, was probably used for target practice by the US. “We were using something out there. I think Scarborough Shoal may be one of the places, yeah.”

“The way I look at China and the US is they are the same banana,” says Custodio. “They are powerful countries ... both are flexing their muscles, their influence... But we don’t really know what happens... We still have the North Korea problem ... We even have Japan which is militarising now ... All of these wild cards thrown in there ... That’s why it’s very important to work within this space that we have now [for peace]. If not, there will be conflict ... If you look at history, the future is not bright for such times of great power rivalries. At a certain point, someone snaps, someone miscalculates and before, when someone miscalculated, at least they throw conventional weapons at each other but now if somebody miscalculates you have the possibility of nuclear war.”

After a few beers, Burnett reckoned nuclear missile launches were unlikely: “Anything they shoot they can knock down most of them – nuclear missiles for example. But there’s nothing [to stop] a merchant ship pulling into San Francisco harbour with a nuke on board - that’s something that’s more difficult to detect.”

Somewhere, possibly in a shipping container, is a loose US nuke, if conspiracy websites are to be believed. “It would take just one vial, one canister, one crate slipped into this country to bring a day of horror like none we have ever known,” warned Bush in January 2003, two months before he invaded Iraq.